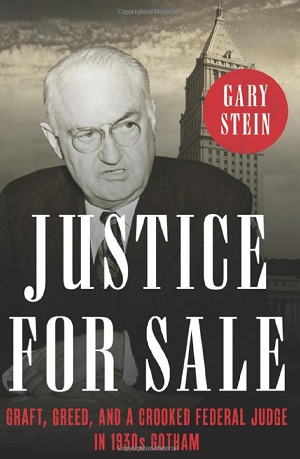

Gary Stein’s nonfiction book has all of the signs of a crime-thriller. Maybe even verging on neo-noir, regardless of its source material being one hundred percent true. In the pages of Justice for Sale: Graft, Greed, and a Crooked Federal Judge in 1930s Gotham, he extensively follows the pursuits and exploits of a one Judge Martin T. Manton, an infamous character who – in the words of his prosecutor – operated something less like a courthouse, and more like a ‘count house.’

The story bleeds timelessness, for better and for worse. And dare I say it, outside of real-life, it offers a fascinating portrait of an unrepentant, unscrupulous, wholly Machiavellian man who capitalized on one of the most infamous and divisive time periods in American history. 1930s New York was the crème-de-la-crème of the social and socioeconomic rot making up the Great Depression – a cutthroat world where racketeering was as common as the age-old death and taxes.

Part of what Stein brilliantly, and chillingly demonstrates, is how certain things pertinent to Manton’s era are still semi-existent today. He shows this, rather than tells it – making the reader draw unsettling parallels between the wholly black-and-white corruption of a time period thirty years after the turn of the century, and its more shadowed form existing today. The book never becomes an out and out political statement, and its strong convictions remain firmly planted in looking through the lens at the time period it so aptly depicts. “Martin T. Manton is little remembered today.

AMAZON: https://www.amazon.com/Justice-Sale-Crooked-Federal-Gotham/dp/1493072560

Yet for the better part of 1939, as the sordid details of his abuse of office tumbled into public view, the saga of Judge Manton took center stage, simultaneously enraging and entertaining New York and much of the nation,” Stein explains. “Front-page reports cycled through the familiar phases of a high-profile scandal: revelation, resignation, investigation, indictment, trial, appeal, imprisonment. Prominent businessmen and lawyers were dragged down in Manton’s wake.

Others were lifted up; Manton’s downfall secured a Pulitzer Prize for the reporter who broke the story, S. Burton Heath of the New York World-Telegram, and helped launch the political career of Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey, the former special prosecutor who originally investigated Manton. Reverberations reached into the White House, where President Roosevelt scrambled to distance himself from the disgraced jurist he previously referred to as an ‘old friend.’”

No one was clean in that time period, and again – showing to some degree the timelessness of the story – Stein brilliantly demonstrates how perhaps, such intrinsic Machiavellian undertones continue to haunt modern systems today. What that says about our society as a whole, that we can continue to relate to the insanities and monstrosities of a time period some would say is a long time ago, is something I find concerning. Particularly considering the fact we are on the precipice of another, anomalous event financially that experts are saying will make the Great Depression in the thirties look like nothing.

One can only imagine the implications of such an event, along with what a modern-day version of a Judge like Manton would do in the face of such implications…

Cyrus Rhodes